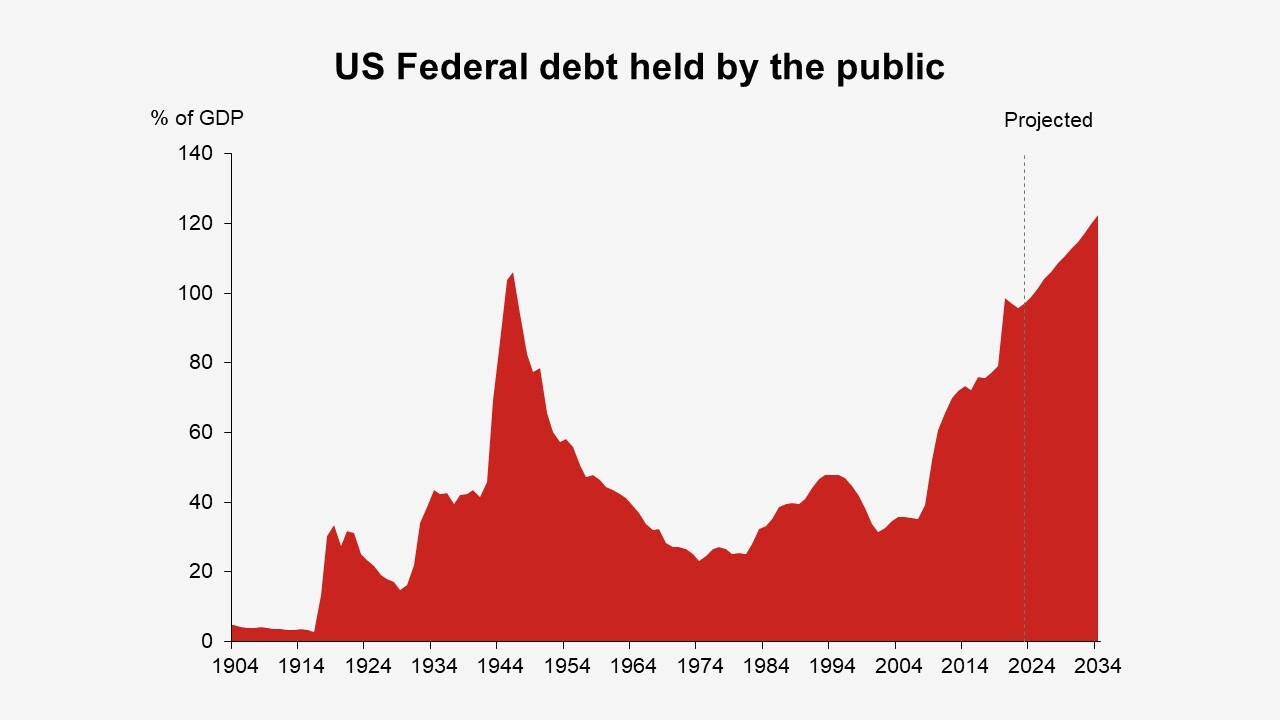

The US fiscal problem is serious, with public debt on an unsustainable path. Last month, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated a deficit of up to US$ 2 trillion, or 7% of GDP, for 2024. The CBO projects federal debt will keep rising to 109% of GDP in 2028 and to 122% in 2034. The pandemic and global financial crisis drove massive budget deficits. In the intervening years, the Fed’s asymmetric monetary policy of very low rates and quantitative easing during weak growth periods, with little reversal when growth recovered, kept government borrowing costs low, providing little incentive for fiscal consolidation.

Fiscal consolidation is becoming more difficult against a backdrop of higher debt servicing costs, an ageing population, deglobalization and rising national security concerns, along with the physical and transitional costs from global warming, according to Nomura analysis. Cutting back on nondefense, discretionary spending in areas such as infrastructure and education could be self-defeating if it weakens economic growth, while reducing mandatory expenditures such as social security and health care will be politically challenging due to the social backlash.

There may be more hope on the revenue side, as America’s tax revenues as a share of GDP are low by advanced economy standards, sitting at 17.2%. The IMF has several recommendations, including eliminating an array of tax deductions and increasing indirect taxes as well as corporate and individual income taxes. In practice, implementing this full menu would be political suicide.

America’s post-World War II experience in resorting to financial repression to reduce its public debt ratio, which reached a historical high of 106% of GDP then, is an unpromising history lesson for current holders of US Treasury debt. The common rebuttal is America’s superpower status means there is no need for it to reduce its debt ratio. As the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, America has gained the exorbitant privilege to run deficits and keep building up debt. Some also point out that Japan has shown that an advanced economy can manage debt of more than twice its GDP.

But America is not Japan. Japan is the world’s largest net creditor nation, while America is a large net debtor. The excess savings of Japan’s private sector easily finance its fiscal deficit. Since the late 1980s, Japan has been stuck in a deflationary, low-growth equilibrium. For much of the last three decades, Japan’s ageing population has been risk averse, lacking dynamism and innovation. It is difficult to envisage America becoming frugal like Japan, forfeiting its dynamism, and channeling much of US private sector savings into Uncle Sam.

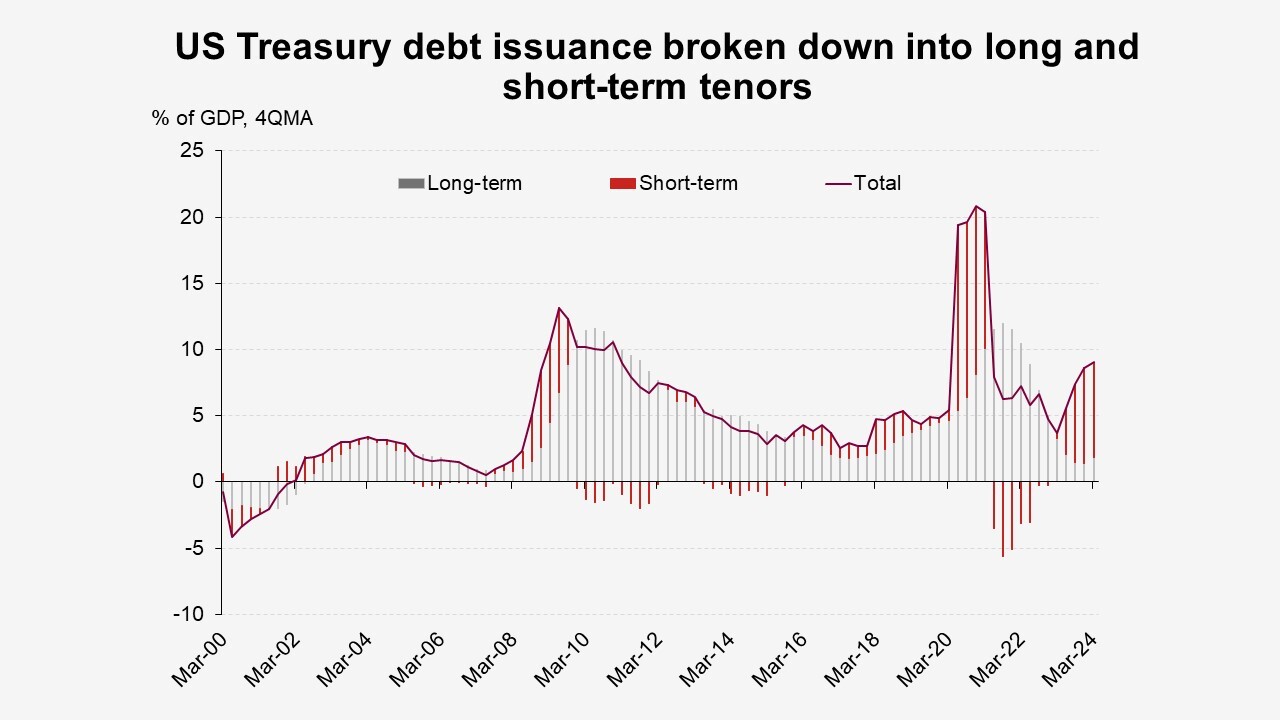

Nor is America’s exorbitant privilege to run deficits set in stone. There has been an ongoing decline in the US dollar’s share of allocated foreign reserves of central banks, ceding ground to non-traditional currencies and gold. The Fed has also been reducing its holdings of US Treasuries. A growing share of US public debt is being held by private sector investors such as mutual funds, banks and pension funds. This can increase the fiscal vulnerability of the US, as private investors tend to be more sensitive to market conditions. Meanwhile, the Treasury last year shifted towards issuing substantially more short-term (1y or less) debt. This could turn out to be a risky strategy if the Fed ends up not cutting interest rates by much, sticking the US Treasury with a higher interest bill or rollover risk, if it shifts back to issuance at longer maturities.

Three scenarios to consider

We have highlighted how in future years it will be difficult to reduce the US fiscal deficit, at a time when America’s exorbitant privilege is showing signs of fraying at the edges. We consider three scenarios for the US fiscal outlook.

- The good: Supported by the generative artificial intelligence revolution, the economy experiences a golden period of strong growth and a return to low inflation. This allows the Fed to cut rates aggressively, by at least 100bp in both 2025 and 2026. On the fiscal front, perhaps helped by the checks and balances of a divided Congress, the next government makes some good progress in reducing the large budget deficit, assisted by lower interest rates and stronger GDP growth. The budget deficits are still large though, and the Federal debt ratio continues to rise, although on a shallower trajectory than the CBO’s projections.

- The bad: Economic conditions are less favorable. Inflation proves sticky and the Fed cuts rates by much less than market expectations in 2025 and 2026. This results in below-trend growth. There is very little progress in reducing the large budget deficit and Treasury faces significant refinancing challenges. Private investors start to demand a higher term premium to buy new longer-tenor Federal debt issuance. An unfavorable fiscal cycle is set in motion, whereby higher government borrowing costs increase its net interest outlays and crowd out private investment, with the latter hurting economic growth and weakening government revenues. All these result in the budget deficit remaining very large, and the public debt ratio rising on a steeper trajectory than the CBO’s projections.

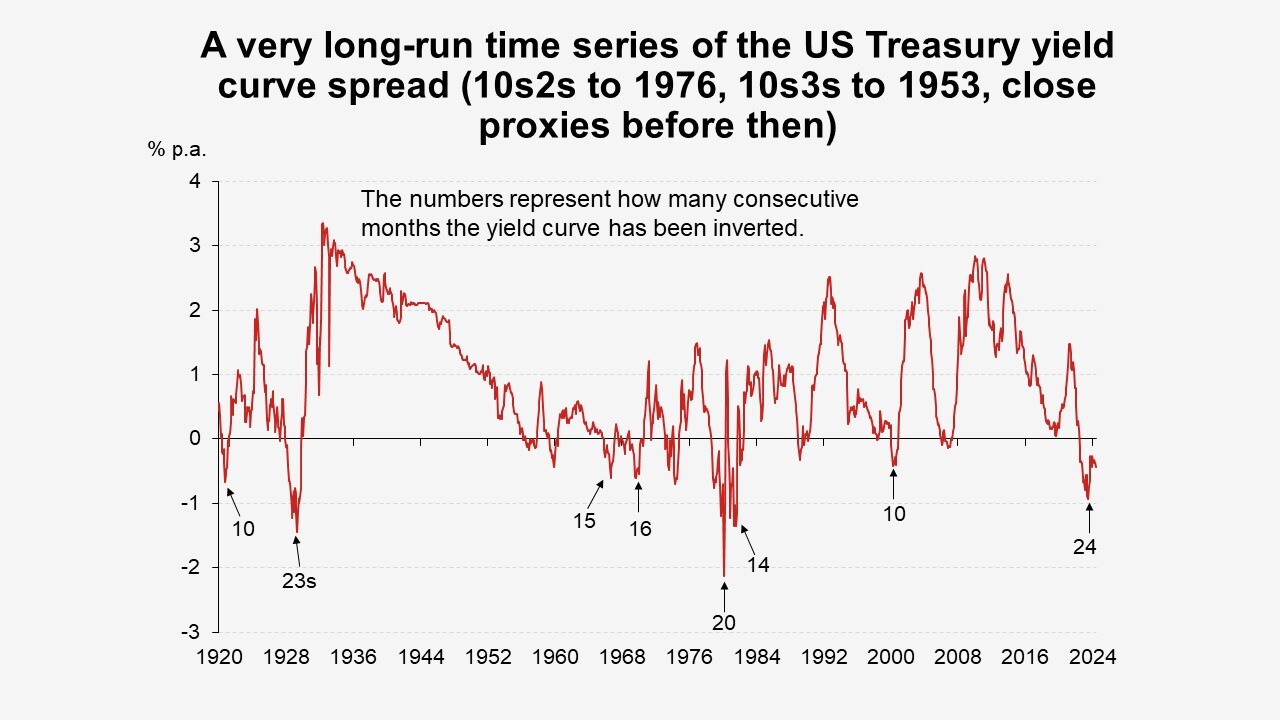

- The ugly: Economic conditions are unfavorable as in the bad scenario but, in addition, US fiscal balances hit a tipping point that is more common among emerging market sovereigns, such as what happened recently in the UK. The private investor base in US federal debt loses confidence in the Treasury, and Treasury loses its ability to borrow at affordable rates. The two dynamics feed off of each other, fueling a fiscal crisis. Some investors may start to entertain the notion of the Fed losing its monetary policy independence and the government enforcing severe financial repression, in a bid to drive real US Treasury yields deeply negative to liquidate the federal debt. In this ugly scenario, the 2s10s spread would likely decompress to levels not seen in a generation. The UST yield curve has already been inverted for an abnormally lengthy period of 24 months; in fact, using historic data from the NBER, we estimate that in June the duration of yield curve inversion eclipsed the previous record of 23 months during the Great Depression.

For more details, read our full report.