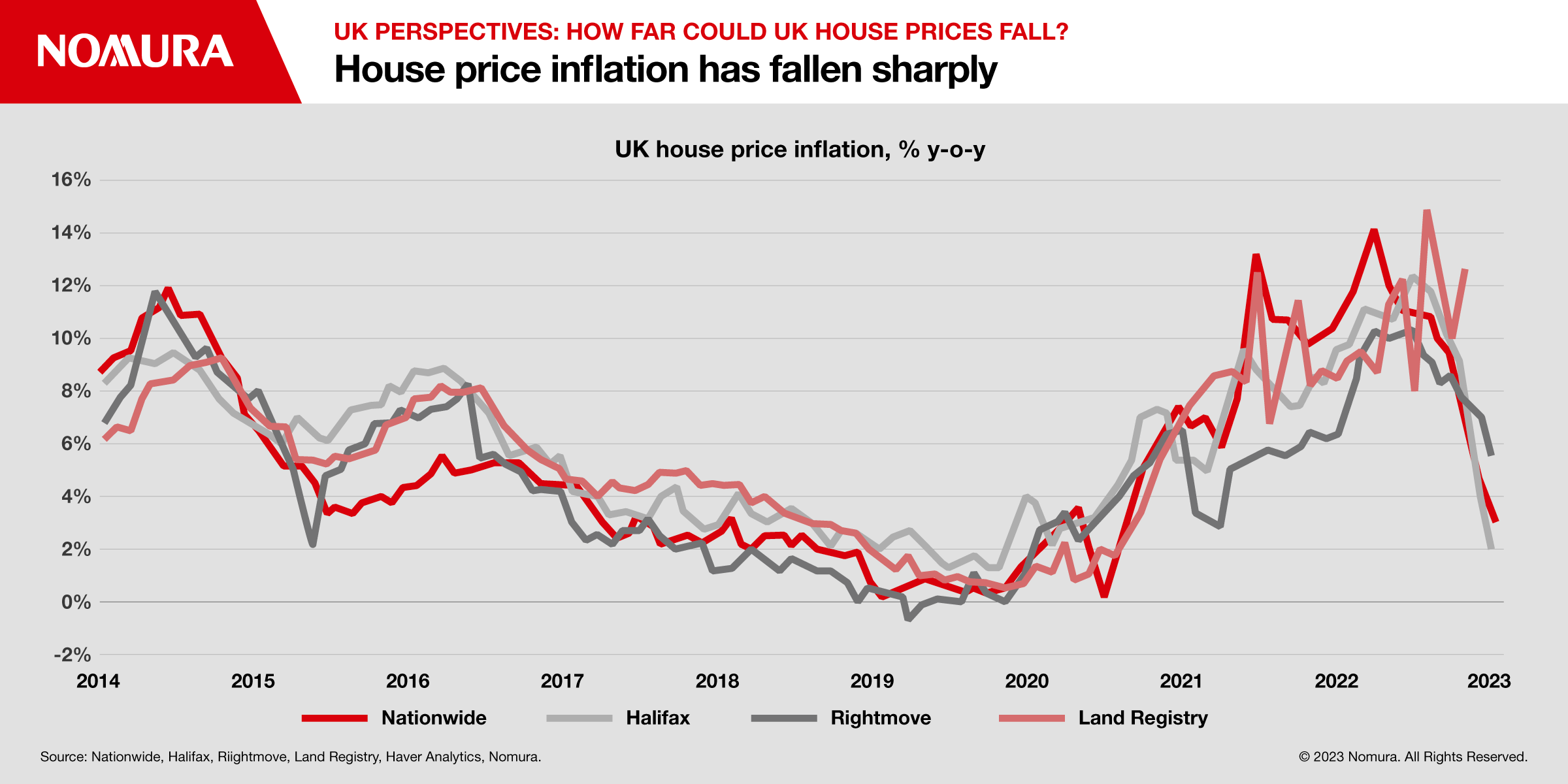

The adjustment in the UK housing market has already started, with mortgage lenders having reported an almost 3.5% fall in house prices since their peak (Figure 1), and mortgage approvals at their lowest level in a decade (excluding the initial Covid-related decline). Regionally, house price inflation has fallen notably across the UK while activity more generally has weakened sharply – as the latest RICS survey reports.

Affordability has deteriorated sharply

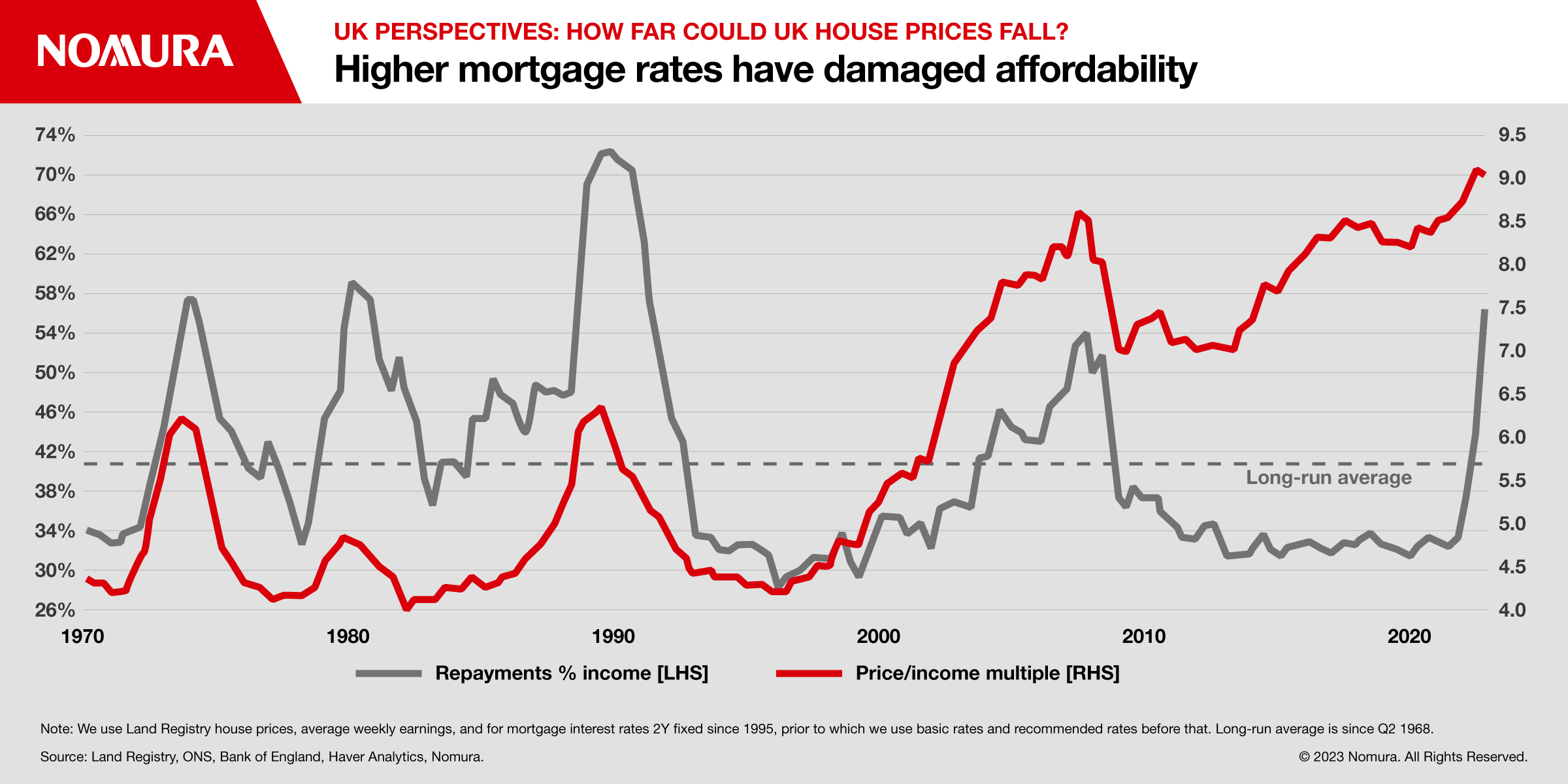

There are plenty of ways one may judge how affordable UK housing is. Among all of these measures we make use of the repayment/income ratio (Figure 2) to calibrate how much UK nominal house prices would need to fall in order to return this measure of affordability to its long-run average in an environment of permanently higher interest rates. After all, 2-year fixed mortgage rates are currently around the 5.50% mark having bottomed at around 1.20% at the end of 2021.

We could see a 15% fall in house prices

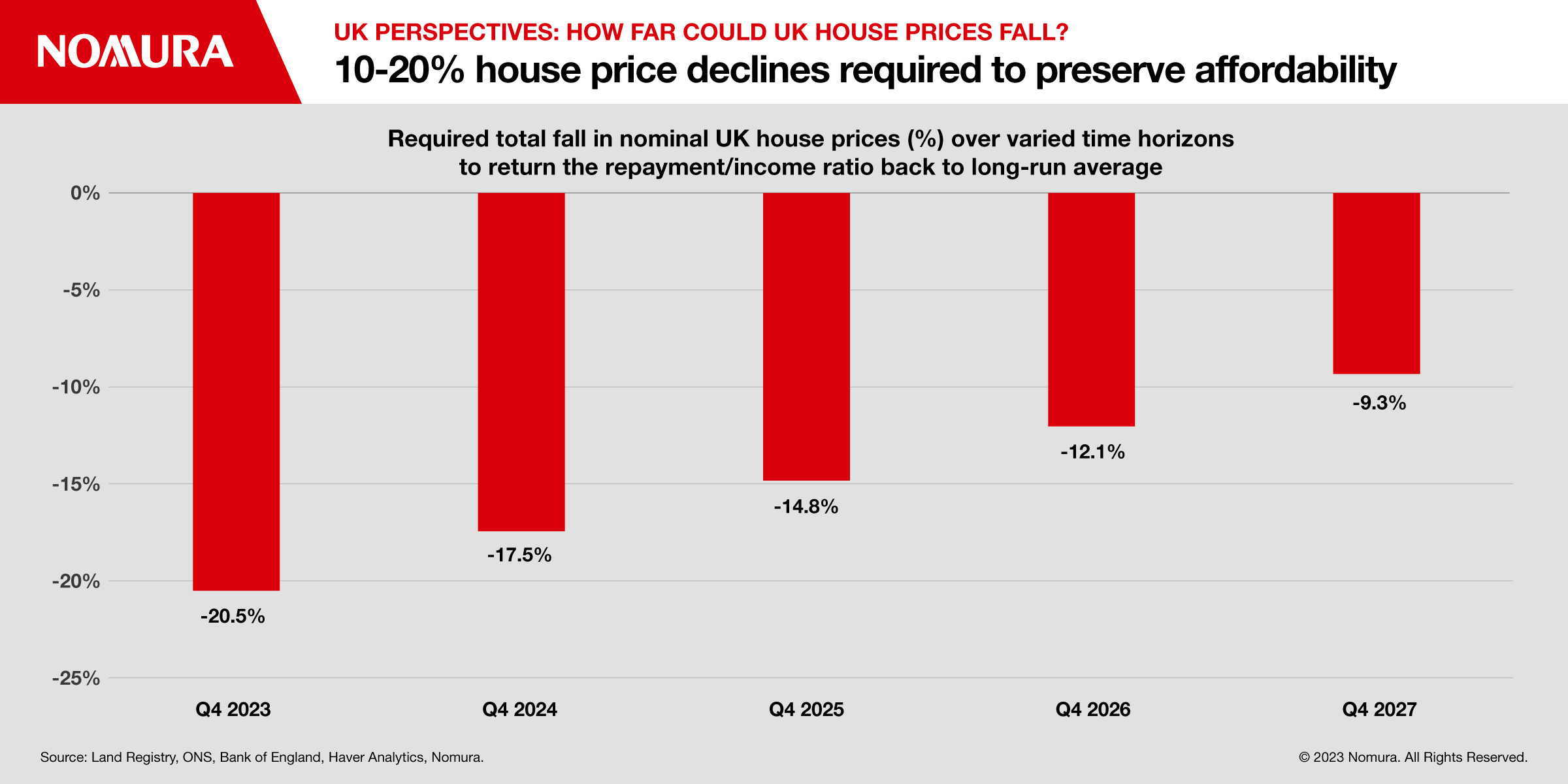

Making reasonable assumptions about the path of wage inflation going forward, and assuming that mortgage rates remain around current levels, depending on the time period over which the adjustment occurs, the peak-to-trough decline required in nominal house prices could be between around 10% and 20% (Figure 3).

We have thus settled on a central forecast of a 15% fall by mid-2024, which while in the middle of the above range would be a larger fall than assumed by the Bank of England, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and consensus. We explore some of the upside and downside risks to this forecast.

The upside risks

There are a number of reasons why the decline in prices might not end up being as large as this. They include: i) the presence of excess savings built up during the pandemic which could be used as deposits on house purchases, ii) the pandemic increasing the desire for residential space, iii) reduced stamp duty rates, iv) ongoing labour market strength, high inflation (which could quickly reduce house prices in real terms without the need for a nominal fall), v) more fixed rate mortgages helping limit forced sales, vi) better borrower creditworthiness than during the last housing crash, and vii) constraints on housing supply.

The downside risks

There are, equally, a number of downside risks too including: i) high inflation eroding real wages and the ability to save for a housing deposit, ii) a grim outlook for the economy (though not quite as weak as the end of last year), iii) the risk of further mortgage rate rises should the Bank of England feel more Bank Rate hikes were warranted to deal with sticky inflation, iv) an ageing population reducing the demand for housing (in the long term), v)more buy to let properties, whose owners may respond to higher financing costs (and thus lower profits) by liquidating their properties.

The housing fallout on the macroeconomy

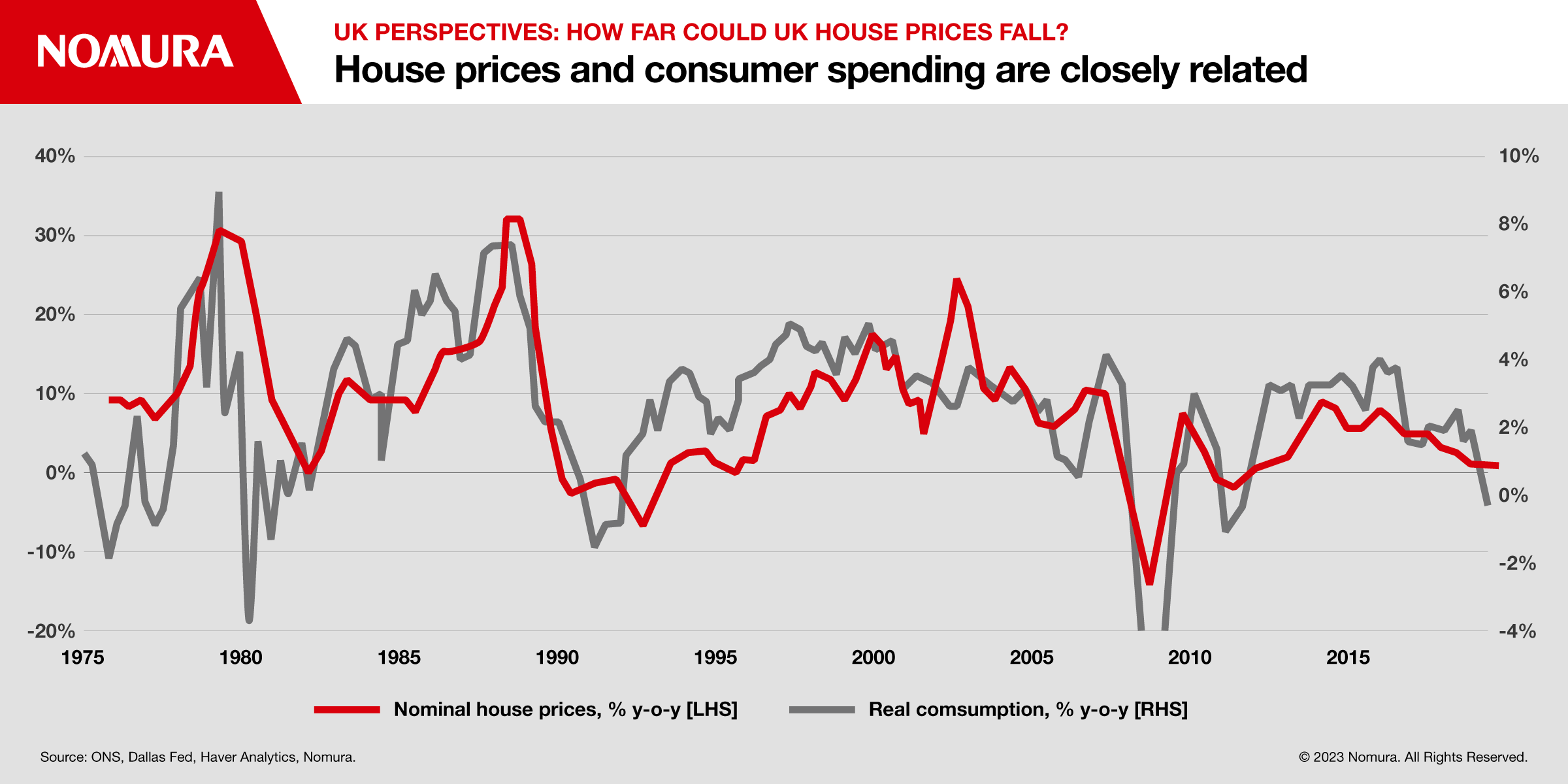

Lower house prices can affect the macroeconomy via two major channels: a) indirectly, as lower house prices tend to be associated with fewer transactions and thus reduced spending on dwelling investment and housing-related goods and services, and through confidence (i.e. wealth effects), and b) directly, via the reduced ability to borrow against housing equity. Lower house prices therefore reinforce our view of an economy-wide consumer-driven recession continuing during 2023 (Figure 4).

Implications for interest rates

The housing market enjoys a symbiotic relationship with monetary policy. On the one hand, the Bank of England (BoE) raising interest rates sharply creates the need for a downward adjustment in house prices in order to preserve affordability. On the other hand, the BoE does not set policy in a vacuum – a weaker housing market (and economy to boot) should provide justification for the Bank to end its tightening cycle soon (Nomura: 4.25% in March) and begin easing policy in 2024 (3.50% by mid-year).