Economics | 22 min podcast April 2021

Economics | 4 min read | June 2021

How are Supply Constraints Affecting the US Labor Market Recovery?

Taking stock and looking ahead

Economics | 4 min read | June 2021

Taking stock and looking ahead

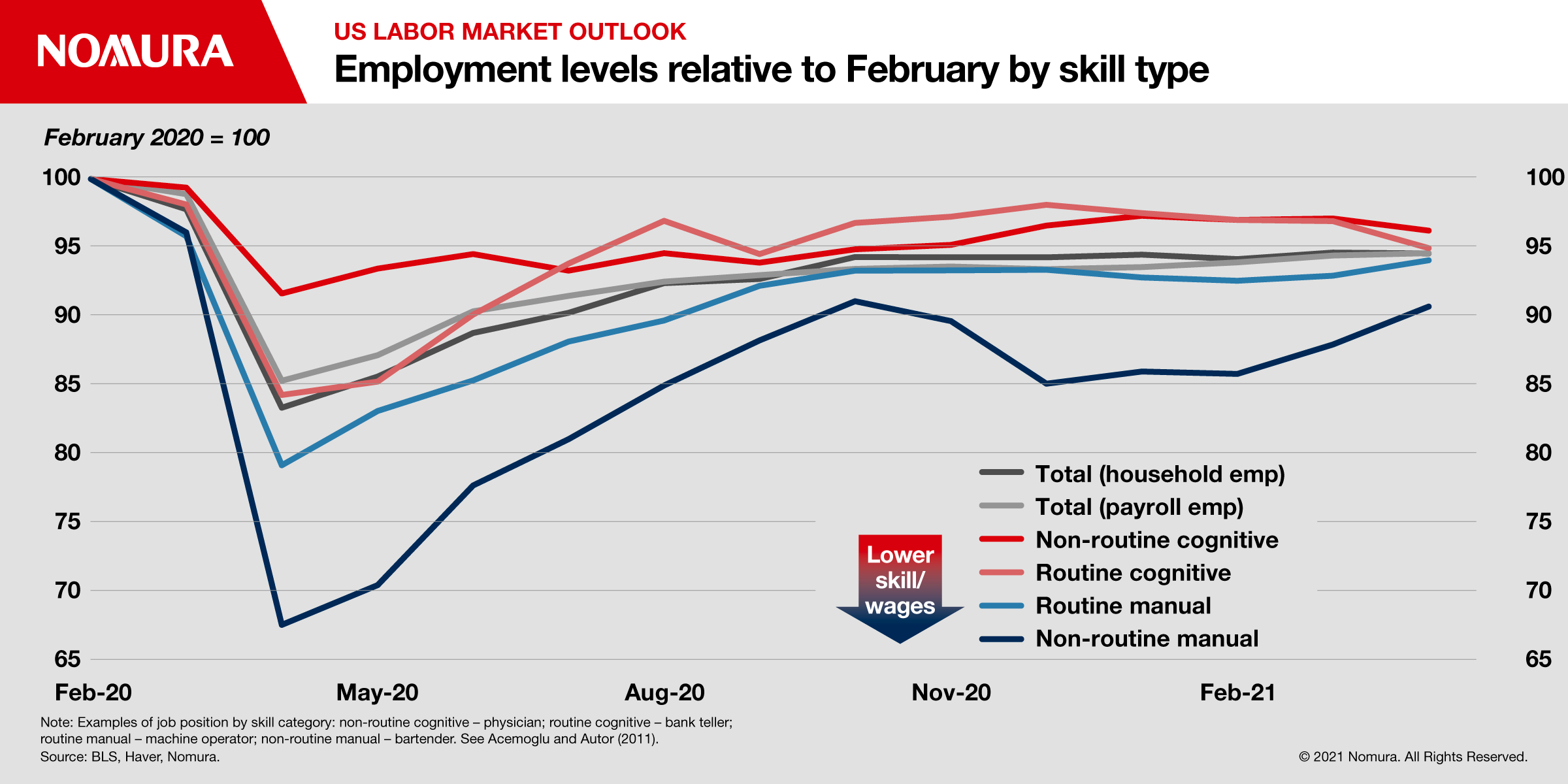

The pandemic recession is one of the largest shocks to the US labor market in history, and it is probably the most abrupt. The impact of the pandemic was especially severe for low-skill/low-wage workers who were concentrated in industries that require a lot of social contact, such as food services, accommodation, arts, entertainment and recreation.

While the nature of the pandemic labor market shock laid the groundwork for a swifter-than-expected initial phase of the recovery, it also had a disproportionate impact on labor supply, which has recently affected how quickly the labor market can recover.

While the labor market recovery has made significant progress over the last 12 months, we remain far away from the strength seen in February 2020. That said, there is increasing evidence that the labor market is tighter than what the employment-to-population ratio (EPOP) and the unemployment rate alone would suggest.

The vacancy rate and quits rate are both at or above pre-pandemic levels. Both indicators suggest a relatively favorable environment for individuals who are willing and able to work. However, we believe the discrepancy between EPOP and measures such as the vacancy rate reflect a significant number of workers facing constraints on their ability to return to their previous job or search for new employment.

The strength in April average hourly earnings (AHE) despite an influx of low-wage leisure & hospitality workers provides some early evidence that employers are responding to labor shortages by increasing wages, consistent with anecdotal information.

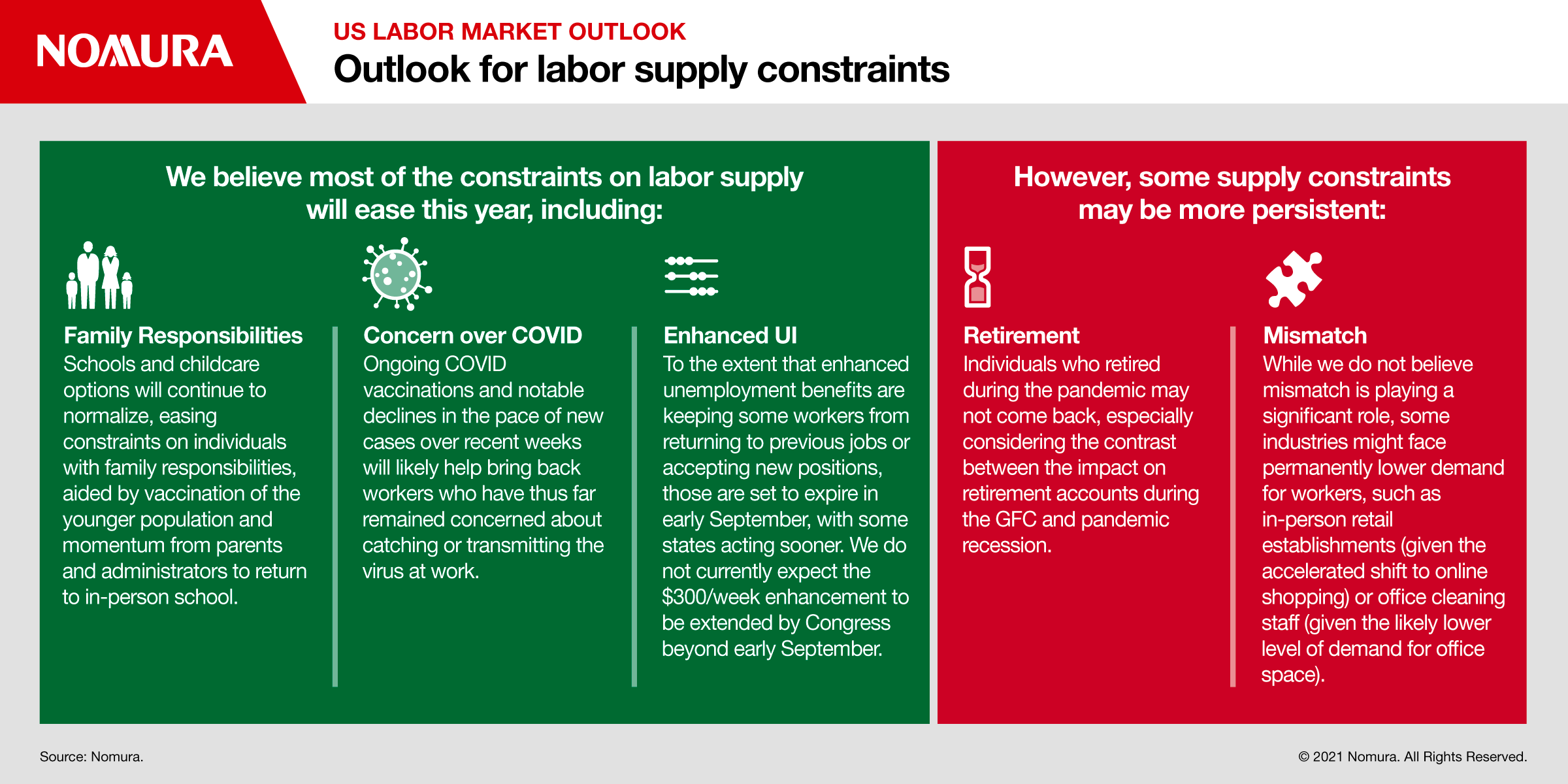

Importantly, we believe many factors contributing to supply shortages are likely to be temporary. As a result, we do not expect a permanent new trend of higher wage inflation.

Finally, the outlook for productivity will also be important for wages. The pandemic shock may have a more lasting positive impact on productivity growth, which could limit concern over higher wage inflation.

The unusual nature of the pandemic recession resulted in a significant number of workers exiting the labor market at the onset of the downturn at a much higher rate compared to the GFC.

Retirement, family responsibilities (amid widespread school closures) and concern over the virus all contributed to a decrease in labor supply. More recently, concern has emerged that $300/week enhanced unemployment benefits are keeping some workers on the sidelines and that a potential skills mismatch is preventing a more robust labor market recovery.

In 2020, temporary unemployed workers were ready to return to their previous jobs once lockdowns lifted; individuals working part time who preferred full-time work could transition back into full-time employment. By contrast, the trajectory of nonparticipants due to family responsibilities will depend on how quickly school and childcare options normalize and vaccine availability for younger children; a large portion of workers who retired since February 2020 may not return; workers concerned over COVID will need to see conditions in their local communities improve along with vaccinations.

We believe most of the constraints on labor supply will ease this year, including:

However, some supply constraints may be more persistent:

Chief US Economist

Senior US Economist

Senior US Economist

US Economist

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.

Jump to all insights on Economics

Economics | 22 min podcast April 2021

Technology | 26 min podcast May 2021

Economics | 5 min read January 2021