Sizeable fiscal loosening has been deployed globally to support economies during the crisis and, as a result, government debt is set to reach unprecedented peacetime levels. Contingent liabilities from government guarantees and loans may yet be called upon, adding to sovereign debt.

Where are the flashpoints?

Some countries have sufficiently low debt, like Germany and Sweden along with commodity-rich nations such as China, Australia and Russia, that we don’t need to worry about them. Gross sovereign debt/GDP ratios in these countries are likely to remain below 75%.

Then there are countries with high – but not excessive – sovereign debt. In Europe, these include the UK, France, Spain and Belgium, with sovereign debt expected around 100-120% of GDP this year. The UK seems most insulated, as it has its own currency and a relatively long average debt maturity.

High-public-debt nations include Greece, Italy, Portugal, Japan and the US (debt/GDP ratios likely north of 130% this year). Being reserve currencies with their own central banks and debts largely issued in their home currencies, Japan and the US do not appear a cause for concern. Italy, on the other hand, presents a risk because of the need for compliance with Europe’s fiscal rules, heightening Euroscepticism which, in turn, could threaten the entire European project.

Do high sovereign debt ratios constitute a relative or absolute problem?

Do debt ratios need to be brought down or can countries permanently operate with higher debt? Should, for example, we be concerned about countries where debt ratios are approaching those of Italy a decade ago? Or is this an “ugly competition’, whereby absolute ratios matter less than a country’s relative position?

The answer is probably a bit of both. Absolute levels matter because these are what govern the ability of sovereigns to repay debt. After all, a rise in interest rates applied to a higher level of debt has a more pernicious effect on debt servicing than when debt is low. Furthermore, high levels of debt are typically associated with lower rates of economic growth, which could disable a country’s ability to achieve debt sustainability.

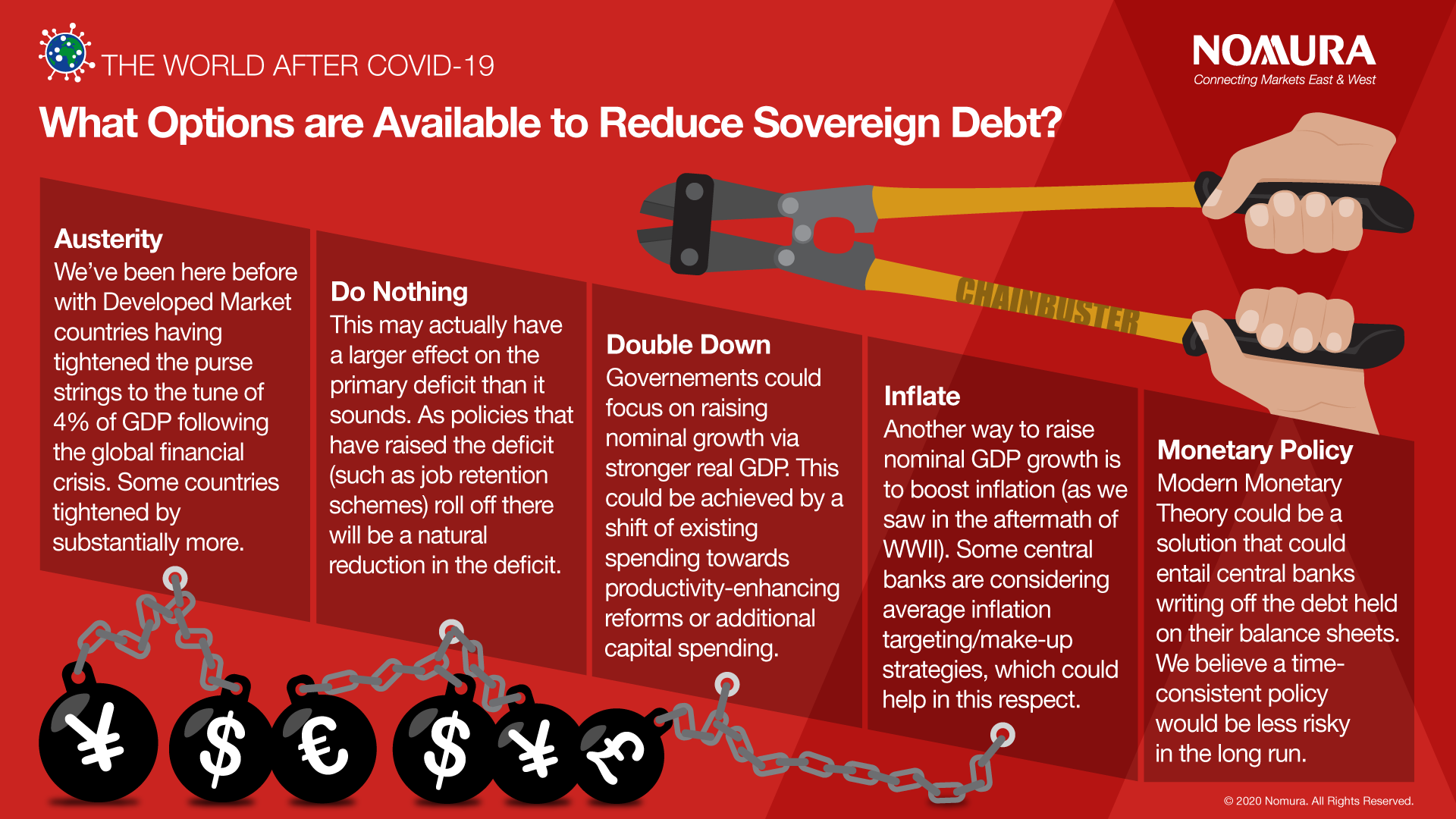

What options are available to reduce sovereign debt?

Let’s say that governments and investors are uncomfortable with the scale of sovereign debt. What options are available to improve fiscal health?

There are a number of reasons we are less worried about the rise in government debt as a result of COVID-19 than the Global Financial Crisis, including the likelihood that interest rates will remain lower for longer and that rising debt has been a consequence rather than a cause of the crisis. Still, a combination of government responses is likely to be necessary to address the rise in debt. After all it would be a mistake for governments to ignore their higher debt ratios on the assumption that funding costs will remain at rock-bottom levels forever.

For further insight on the world post Covid-19, read our full report here.