US Water Wars – How Climate Change is Driving Water Scarcity

Megadroughts in some US states could be a recurring phenomenon yet they offer a chance to revitalise a dated and inefficient water system.

- Lake Mead, America’s largest reservoir hit its lowest level since it was first filled in the 1930’s

- President Biden’s infrastructure bill promises $8.3 billion for Western water storage

- Most water technologies such as drip irrigation focus on efficiency and conservation

Record-breaking droughts that threatened to paralyze Western US states this year are a warning that urgent action is needed to reverse global warming and invest in solutions for better water security.

A US government report from September confirmed that human-induced climate change intensified the drought in States from California to Arizona, making it the region's most severe on record, with precipitation at the lowest 20-month level documented since 1895.

Current anthropogenic trends in temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation have caused the period from 2000 to 2018 to be the driest 19-year span since the late 1500’s according to Science.org. These so-called megadroughts have caused reservoirs to dry up, with America’s largest, Lake Mead, heading, in June, to its lowest level since it was first filled in the 1930’s.

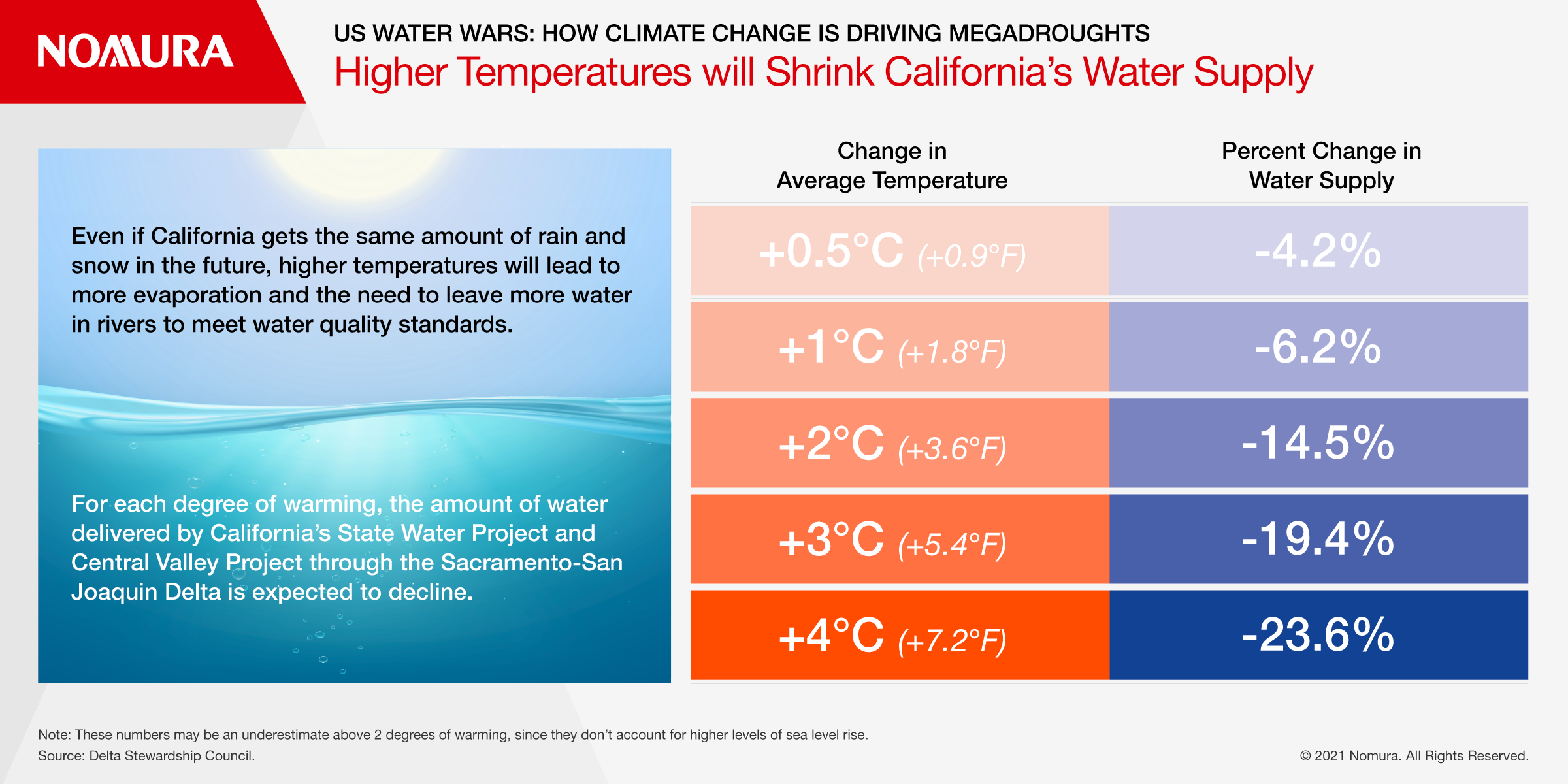

And it could get worse. The flow of the Colorado River – which services 40 million people - is expected to shrink by 9% for every degree Celsius of warming.

Those who manage the West’s complex water systems realize they can no longer rely on the historical rainfall trends of the past to secure the future. Instead, the norm is more likely to be record low precipitation, combined with record high temperatures resulting in devastating droughts.

Fertile Ground

With the agricultural sector consuming more than 70% of available water supply, this new normal would jeopardize the fabric and livelihood of the Western states. California alone supplies one-third of all vegetables in the US, and two-thirds of all fruits and nuts.

The water system in the Western states is built around three main storage systems: reservoirs, groundwater and snowpack.

The region’s farmers may be praying for a big snowpack this Winter as insurance against a scorching Summer but rising global temperatures could banish those hopes. It’s creating uncertainty about what crops to plant, which in turns leads to less planting, risking steep price increases in staples like garlic, tomatoes, and onions. The water shortage has already caused some almond farmers to rip out older trees and replace them with younger varieties that require less moisture.

``The historic droughts in the Western US show the bleak realities of climate change and the urgent need to secure the water supply,’’ says Jeff McDermott Global Co-Head of Investment Banking at Nomura. ``Rising temperatures mean we need to invest in the technologies and infrastructure that will ensure we have water even in an extremely dry Summer.''

The water system in California and across the Western states remains stressed, complex, and outdated. "California's water system was designed for a climate we don't have anymore," Alvar Escriva-Bou, a research fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, told National Public Radio. "What we are seeing, especially in some parts of California, is that we have been using more water than we have. And that's causing problems. So the reality here is that we have to make a reduction of water use over the long term."

Water Fights

Water reduction, and infrastructure innovations, rely on understanding the West’s complex legal relationship with water, and how it needs to evolve with climate change.

Water access is controlled by property rights and all water supply in the West is legally claimed, or projected to be by 2030. New water demands can frequently only be met through reallocation of existing rights. Legal conflicts often centre around two main issues: the no injury rule, which prevents water transfers from causing any change in water availability to other water rights, and defining the amount of water that may be transferred with actual historical water usage which can be disputed or is largely unknown. This legacy legal system is not equipped to answer new and unprecedented water needs due to climate change.

The Colorado River Compact of 1922, for example, divided the river into Upper and Lower Basins, and allotted each basin for future management. But the irrigation framework was based on an overestimation of the river’s future water supply making it inflexible in the face of new droughts. These strict legal frameworks result in intense disagreement and disparity within communities vying for water allocation. For example, the Klamath River Basin at the California-Oregon border is allocated across two different indigenous tribes and farmers in the region. Each interested party has its own reasons to access this water source: the Yoruk tribe needs water to flow to the Klamath River to protect the Coho salmon population, the Klamath tribe needs water to stay in the lake to protect endangered fish species central to their culture.

Water shortages, combined with strict legal frameworks can perhaps be best summed up by Vice President Kamala Harris’ warning that we are entering a period of conflict for scarce resources. “For years there were wars fought over oil; in a short time there will be wars fought over water,” she said.

In a further sign of how severe water scarcity has become in the Western states, the financial markets spotted an opportunity to offer a hedge against drought risk. In December 2020, CME Group launched a futures contract based on the Nasdaq Veles California Water Index (ticker symbol H2O). The index tracks the price of water rights, leases and sales transactions across the five largest and most actively traded regions in California.

Infrastructure

All of this signals that new ideas and investment are required sooner rather than later.

President Biden’s infrastructure bill is a good start. It promises $55 billion in water infrastructure with a further $8.3 billion in Western water infrastructure. A key plank of the water policy aims to eliminate the nation’s lead service lines and pipes, delivering clean drinking water to up to ten million families and more than 400,000 schools and child care facilities that currently don’t have it, including in Tribal nations and disadvantaged communities.

Solutions

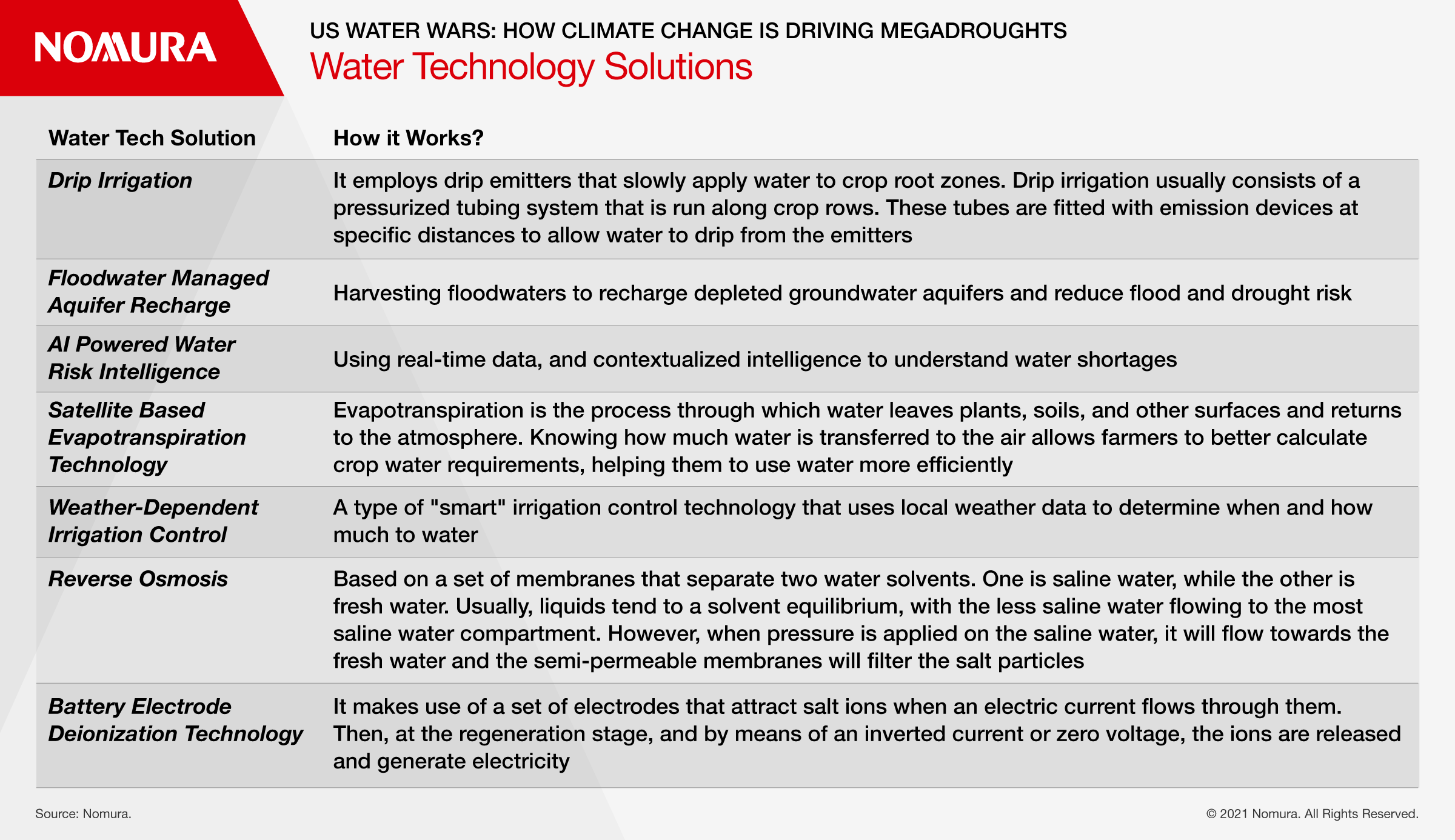

In response to worsening drought conditions, the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) was passed in 2014 to help protect long term groundwater resources. SGMA requirements, while environmentally friendly, place limits on farmers who are being forced to look at alternative solutions. The most important drivers of water technology are efficiency and conservation.

One approach is to harvest floodwater to augment water supply. Managed aquifer recharge technologies supply more water for agricultural needs through recycling, while tackling a trio of problems: flood risk, drought risk, and groundwater overdraft risk. With current and future climate change intensifying the hydrological cycle, increased variability of precipitation and runoff results in more frequent and more severe droughts and floods, as well as the swings between them, sometimes called ‘whiplash events’ by scientists.

In June the Buffalo Sewer Authority issued a $54 million Environmental Impact Bond, to fund the design and implementation of green infrastructure to capture storm water, and reduce sewer overflows.

‘’The dual threats of heightened drought and flood risk require transformational changes to existing water management practices,’’ says McDermott.

Another solution comes by farmers switching from flood irrigation methods to micro and drip irrigation that delivers water directly to the root systems, which reduces evaporation rates. The technology is adapting to the changing risks, and the investments must follow suit.

Farmers in the Western states may also need to turn to Evapotranspiration technology, as such a large proportion of water usage is for crop irrigation and food production. Most of these technologies translate into data: allowing farmers, municipalities, and businesses to use facts and figures to optimize existing resources.

If droughts persist, desalination technologies may also gather steam. In June, the city of Fort Bragg approved the purchase of a 1,090 cubic metres per day reverse osmosis plant from Aqua Clear to treat saline river water. Reverse osmosis removes the salt and other effluent materials from water.

``California plays a critical role in food production, which has to be safeguarded,’’ says McDermott. ``Desalination and water efficiency technologies are vital in the fight against crippling droughts when every drop counts.’’

Peter Gleick, scientist and President of the water-focused research nonprofit, the Pacific Institute, noted during an Emergency Briefing in September that “water efficiency and conservation has enormous potential to cut the amount of water we need to do what we want. We can turn the current crisis into action’’, he said.

Survival

Climate change mitigation is no longer a future problem. The megadroughts that scientists predicted in years to come, are on our doorstep, impacting every facet of Western agriculture, sustainability, and economic wellbeing. As we head towards 2022, we must place importance in altering strict water laws that inhibit flexibility, while investing in water technologies for agricultural prosperity. Water in the West is in survival mode but through scientifically informed investments, policy changes, and conservationist mindsets, we will see the birth of a more resilient water system.

Download full article here

Contributor

Jeff McDermott

Global Co-Head of Investment Banking at Nomura Holdings

Disclaimer

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.