How New ESG Transparency Rules Will Unleash the Next Green Wave

Regulators across the world are revamping ESG disclosure rules to reduce greenwashing and catch up with demand from investors struggling to decipher how green their investments truly are.

- The current patchwork of largely voluntary ESG disclosure regimes makes it difficult for investors to make meaningful comparisons, which holds back the market

- The US, EU and Japan are proposing stricter mandatory rules and efforts are underway to create a global standard setter

- The Global Financial Markets Association estimates that limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires average annual investment of $3–5 trillion

As the climate warnings have grown louder, the pace of ESG inflows has increased, yet claims of greenwashing haven’t allowed the industry to fulfil its potential. That’s set to change as regulators across the globe mandate ESG transparency rules, which could trigger the next leg up in the green revolution.

Money managers from New York to London to Tokyo have been left scratching their heads as prominent financial firms have been called out for alleged ‘greenwashing,’ the practise of embellishing their ethical credentials.

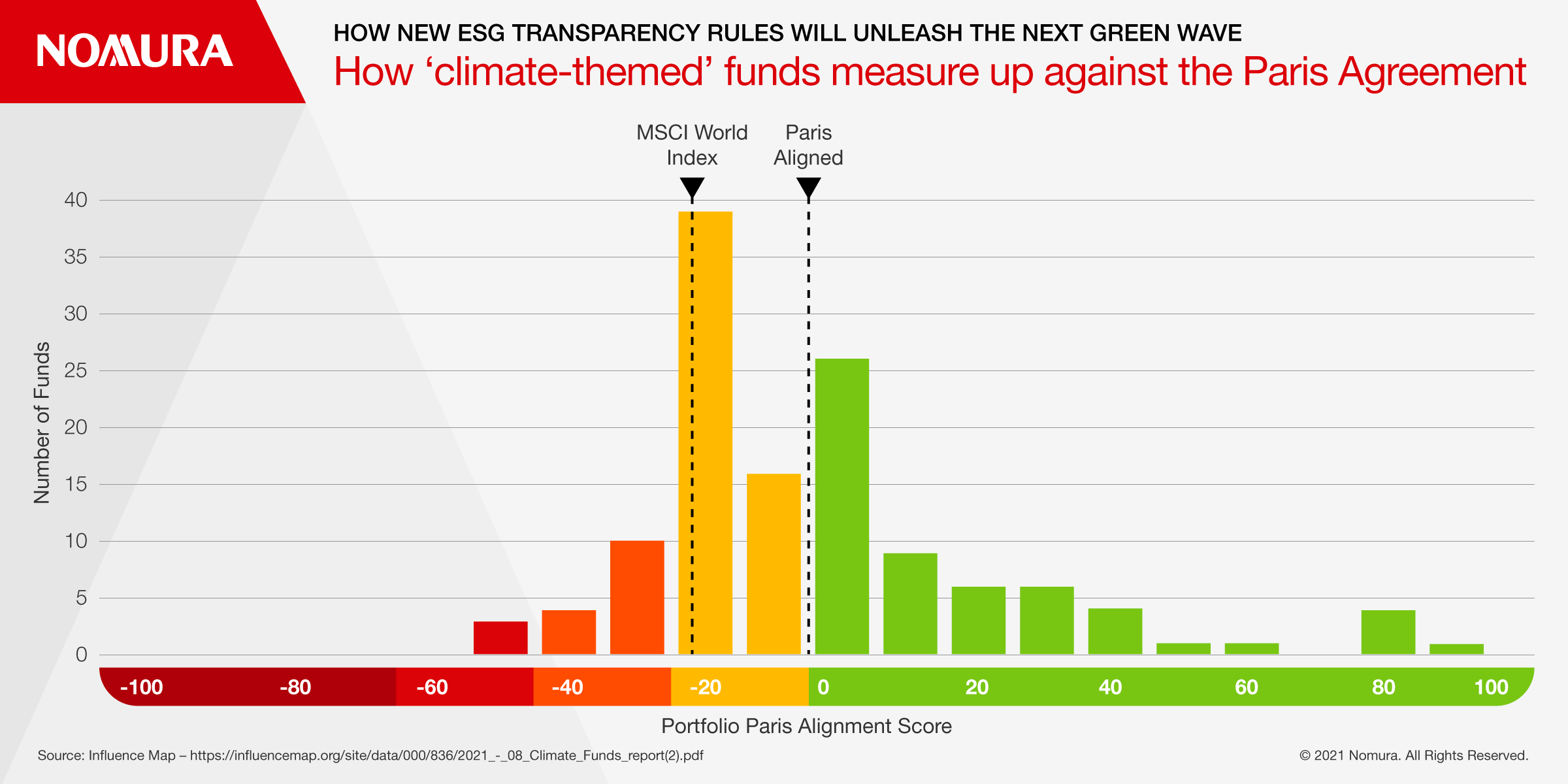

Think tank, Influence Map, released a report in August revealing that about 72 of the 130 climate-focused funds it examined — which collectively hold more than $67 billion in assets — were found to be misaligned with the Paris agreement goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius.

Meanwhile, a new study by Paris-based EDHEC Business School found that despite asset managers talking extensively about the use of climate data to construct their portfolios, these data points represent at most 12% of the determinants of portfolio stock weights on average.

EDHEC said that the current system places greater emphasis on non-environmental factors like financial results, and that to promote true alignment with climate objectives, fund managers should put pressure on industries to reduce greenhouse gases.

At the heart of this discussion is the challenge that ESG screening for firms is largely self-determined, producing varying outcomes. Without standardised disclosures, the job of asset managers becomes an imprecise science.

And regulators have taken note. Japan overhauled its corporate governance code this year and plans to bring in mandatory ESG reporting. Europe has already introduced phased rules for green funds followed by stricter sustainability reporting for public companies from 2023. Similarly, the US plans to introduce specific ESG rules for public company disclosures and ESG funds for the first time.

"Voluntary disclosure regimes have made it difficult to compare and benchmark companies, which slows down the investment decision-making progress. Investors allocating capital in a knowledgeable way around ESG metrics can have a profound impact on the sustainability transition."

US

For Gary Gensler, the newly appointed head of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, the tipping point came this year when investors submitted comments on the SEC’s disclosure rules.

In a July speech, Gensler noted that the agency had received more than 550 unique comment letters responding to its proposal for reforming climate rules, 75% of which supported mandatory disclosures.

Materiality

At present, the US reporting system for ESG is voluntary. The SEC requires public companies to reveal information that may be ‘material’ to investors defined as ‘a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person would consider it important.’

That approach appears to lag investor expectations. In December 2020, Refinitiv commissioned a comprehensive survey of over 600 institutional investors globally, which found:

Exactly what data investors will receive, hinges on whether the SEC expands its definition of ‘materiality’. In one comment letter, the Alternative Investment Management Association favoured a focus on core climate disclosures rather than a more expansive approach ‘to create momentum in the market and ensure progress is made’.

Europe has embraced the broad definition of ‘double materiality,’ which encompasses how sustainability issues affect the company, and on the company’s impact on society and the environment.

The SEC is also considering how disclosures should be filed including whether to use 10-K forms (annual reports).

Gensler said that investors are looking for ‘’decision-useful’’ information. That includes both qualitative metrics such as board strategy and quantitative measures like carbon exposure.

Some firms currently volunteer so-called Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gas data. These refer, respectively, to the emissions from a company’s operations, and use of electricity and similar resources.

Scope 3 covers emissions across the value chain such as when an oil company sells its product as fuel used by cars on highways.

``As soon as companies start consistent ESG reporting, and Boards note that some are less competitive versus peers, they will try and lower their carbon footprint,’’ says McDermott. ``There’s a huge environmental benefit in going from brown to green. Sustainable technologies are now sufficiently cost effective that it’s profitable for ESG laggards to become lower carbon and more resource efficient.’’

The SEC also plans to hold firms more accountable to their net zero pledges. Some don’t currently tie such promises to any scope 1-3 emissions, yet 92% of companies in the S&P 100 plan to set emission reduction goals. It is considering requesting metrics that companies can use to inform investors about how they are meeting self-imposed targets.

Given the significance of mandating ESG disclosure rules, change won’t be immediate. The SEC is expected to release its proposal later this year with the rules taking effect as early as 2023, which seems likely to coincide with Europe’s efforts.

Europe

European companies have already been required to report ESG information in the Non-Financial Reporting Directive since 2018. But companies operating inside the 27-nation bloc will have to comply with stricter rules under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) from 2023.

CSRD will significantly enhance the scope of the existing provisions to cover all large firms plus those listed on EU regulated markets except micro-entities. That will increase the number of companies captured to 49,000 from about 11,000 currently.

It introduces new requirements to provide details about strategy, targets, the role of the board and management, the principal adverse impacts connected to the company and its value chain, intangibles, and how they have identified the information they report.

It also specifies reporting forward-looking targets across different time horizons.

Japan

The Tokyo Stock Exchange revised its governance code in June to advance sustainability as part of a broader reorganisation that will streamline market segments from five at present to three from next April: Prime, Standard and Growth Markets.

The Prime market, which attracts institutional investors will impose a higher standard for companies seeking a listing. Requirements will include providing information on investments in human capital and intellectual property as well as a commitment to sustainable growth. Prime Market companies should also collect and analyze data on the impact of climate change-related risks and earnings opportunities on their business activities and profits, and enhance the quality and quantity of disclosure based on the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) rules or international equivalents.

In September, Japan’s Financial Services Agency started discussions to make climate-related reporting mandatory, and draft rules are expected to be published in 2022. The regulator is focusing on single materiality that targets financial significance.

"Japan is playing its part in making environmental information more transparent, global consistency would make the analysis process even more efficient for investors."

Global Standard Setter

Earlier this year, the International Organization of Securities Commissions announced that the SEC was working on technical standards to support the IFRS foundation’s plan to develop a Sustainability Standards Board (SSB).

Such a unifying move has the potential to add huge momentum behind efforts to increase company disclosures and transition heavy industries by simplifying the reporting process.

The SSB would potentially merge standards from the TCFD, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the Global Reporting Initiative to create an initial framework by the middle of next year. The plan could mean, for example, that greenhouse gas emissions reporting is globally consistent.

For much of the past decade, the onus has been on governments to solve the climate crisis. But with clear regulatory frameworks in sight, the groundwork is being laid for the baton to be passed to the private sector, which has far greater resources to devote to the sustainability transition.

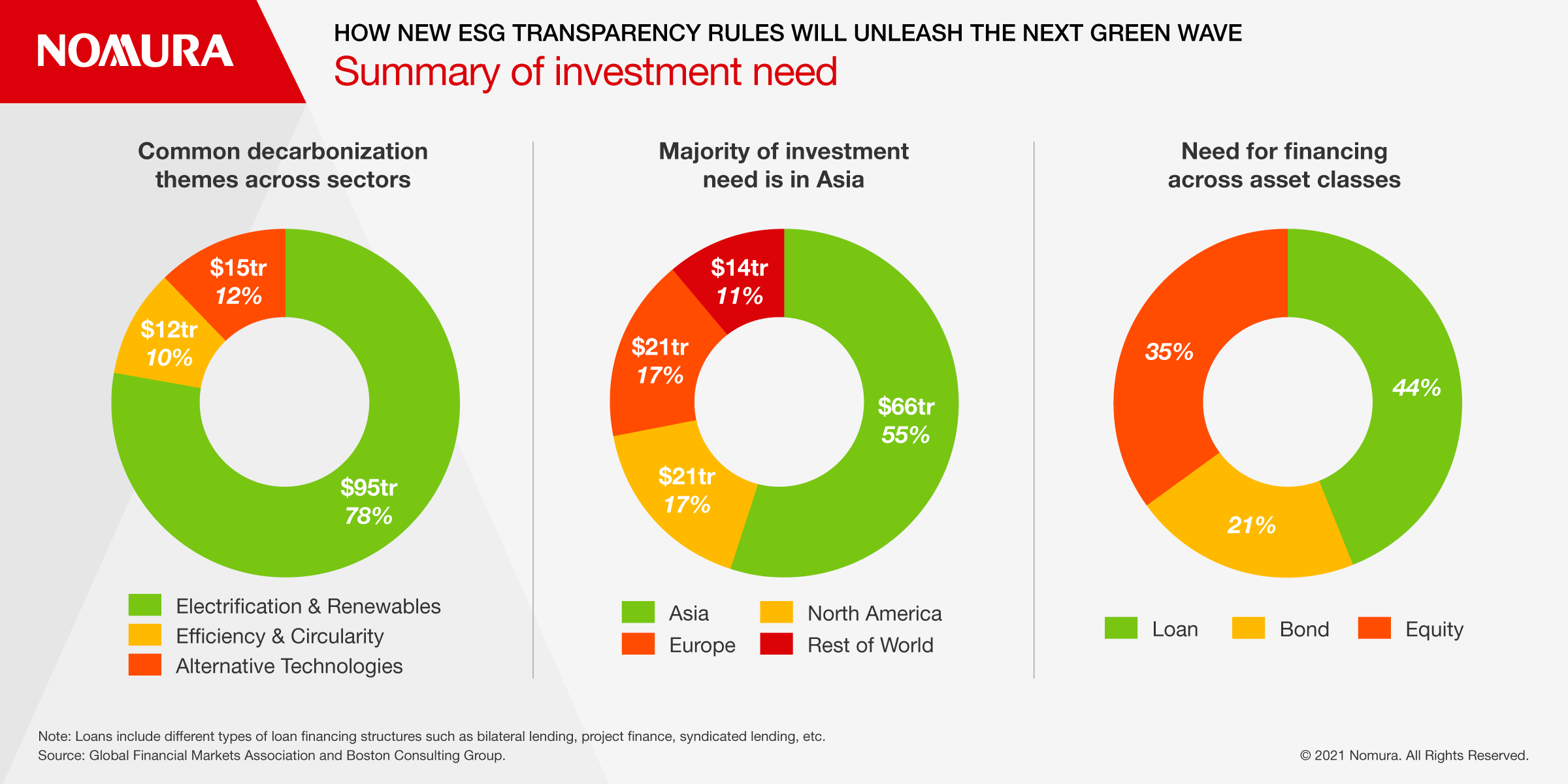

The Global Financial Markets Association estimates that limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels requires average annual investment of $3–5 trillion, or $100-150 trillion through 2050. That would decarbonize 10 sectors that represent 75% of global emissions

In general, bringing greater transparency to corporate sustainability should lead to greater confidence and credibility among investors, asset managers, and executives, according to McDermott.

``Having a reporting framework in place that allows the free markets to better perform their role of efficiently allocating capital to the most sustainable companies could ultimately create a ‘race to the top. Companies will have a greater incentive to have high ESG ratings in an effort to attract investor support and favorable financing terms.’’

Contributor

Jeff McDermott

Global Co-Head of Investment Banking at Nomura Holdings

Naotaka Itazu

Senior Analyst at Nomura Institute of Capital Markets Research

Disclaimer

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.