What causes a sovereign debt crisis?

Debt becomes unsustainable when investors no longer believe a government can pay it back. It is not just the current level of debt that is important but also the plan the government has in place to repay it. The feasibility of such a plan depends on the path of growth, inflation, interest rates and fiscal policy. If these variables become incompatible with stable debt in the long-run, investors will doubt the ability of a government to pay their debt and the risks of sovereign default may escalate.

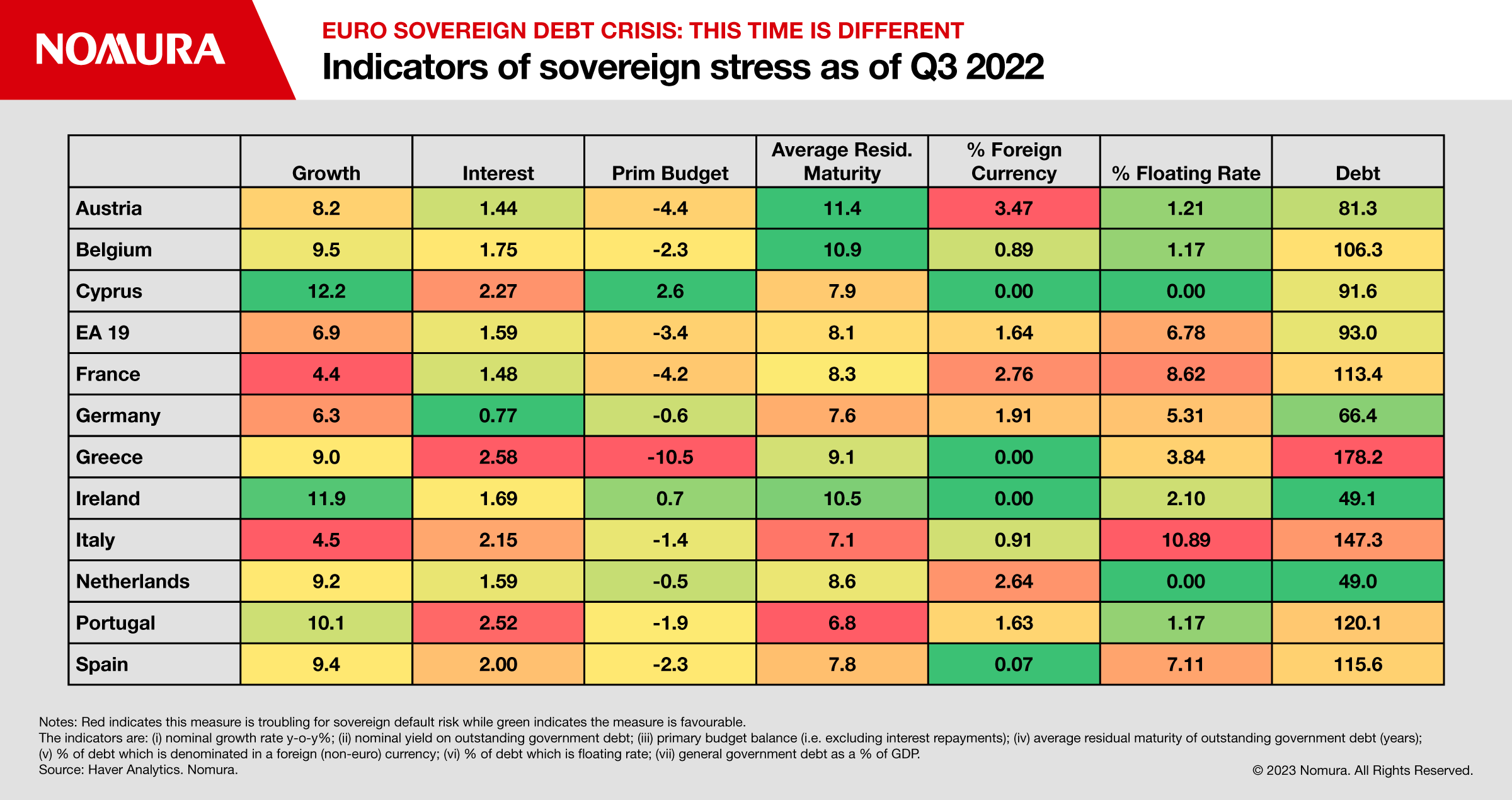

At the start of the European debt crisis of 2009-15, the euro area countries were clearly in a sticky situation. Nominal growth rates were mostly negative - except for Austria and Belgium, interest rates on debt were relatively high and most economies were running structural budget deficits.

Why is this time different?

For now, the risk of a sovereign default appears to be low thanks to inflation keeping nominal growth rates high. Although the ECB is raising interest rates, debt servicing costs remain low and it will take a long time for higher central bank rates to feed through into higher borrowing costs. The average nominal yield on outstanding debt for the euro area was only 1.6% in Q3 2022 in comparison with 3.6% in Q4 2009.

However, as these effects reverse, the risk climate could change. 10 out of 12 euro area economies are running primary budget deficits and the fiscal balance does create vulnerabilities.

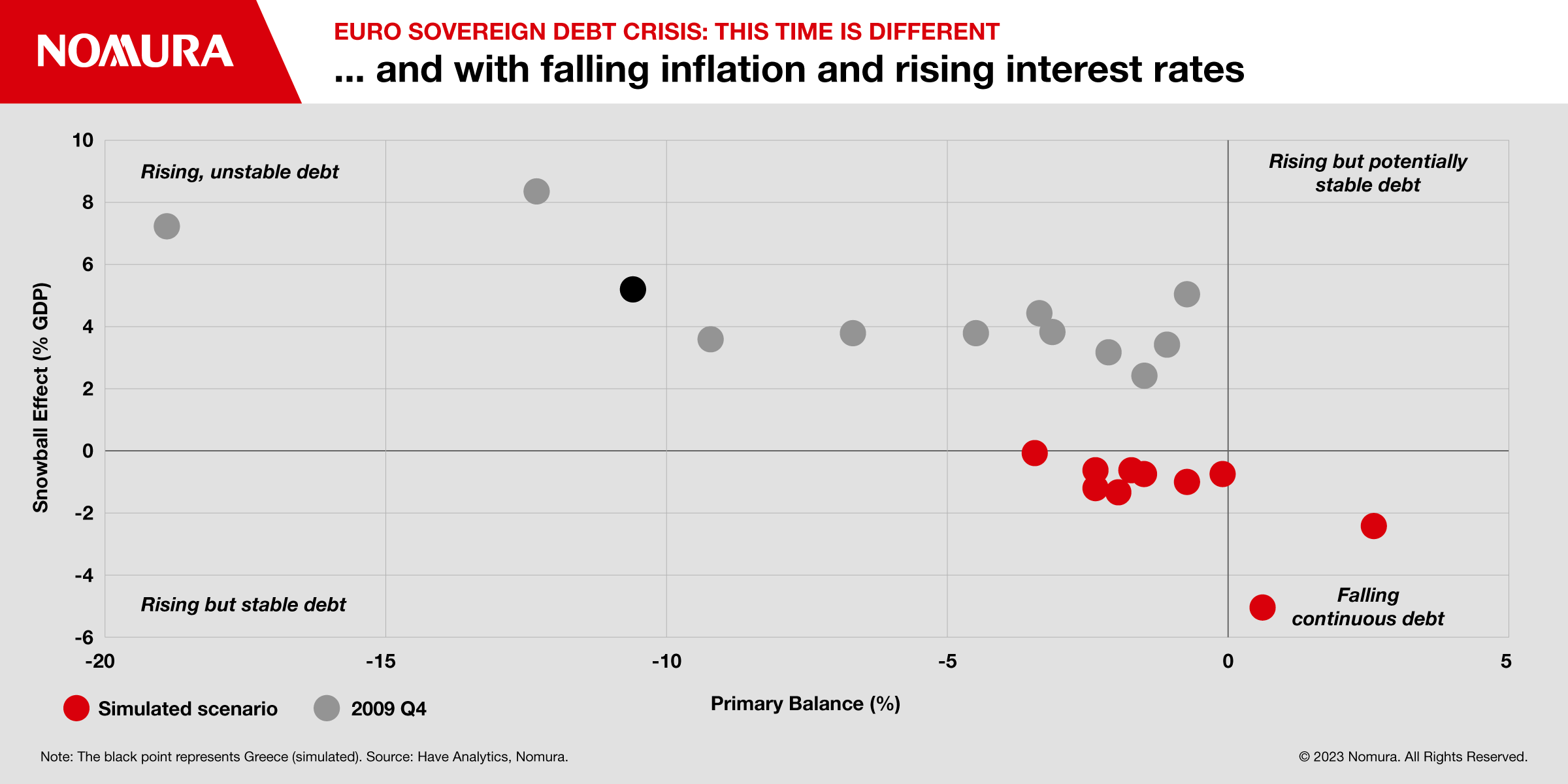

We expect nominal growth for the euro area to return to 3.3% (the trend level) in 2024 from 13.1% in 2022, largely due to a fall in the headline rate of inflation. It is also reasonable to assume that as the ECB continues to raise rates, this will raise interest rates on government debt - much of this has already been priced into sovereign yields.

We simulate this effect below (Figure 2) to show that the risk of a sovereign default could heighten in this scenario but remains far from the levels before the last sovereign debt crisis. Many countries are only just in the ‘danger zone’ (top left quadrant).

Assessing fiscal space

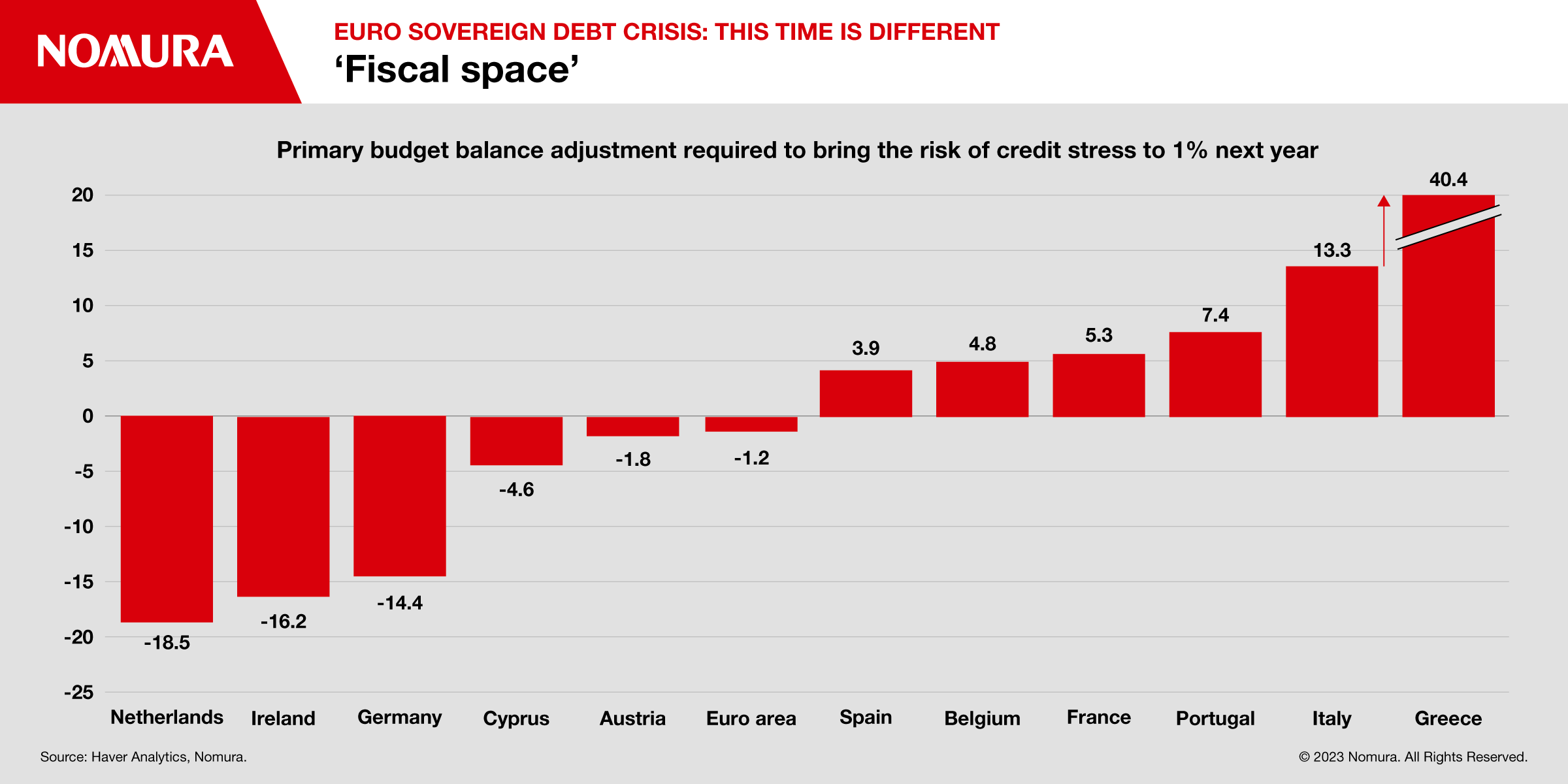

We have created a model for assessing how much a government should adjust its fiscal policy to remain on a sustainable debt path. Figure 3 shows the adjustment that would be required in a country’s primary budget balance to keep the probability of sovereign stress below 1%. Clearly, some countries including Greece, Italy and France, would need to make big adjustments over the next couple of years if they want to reduce the risk of default.

But for other countries, they already have plenty of fiscal space because they have a very low risk of default currently. The model suggests that Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany and Cyprus may actually increase spending and still keep the risk of sovereign stress below 1%.

Implications of Next Generation-EU Funding (NGEU)

During the pandemic, EU leaders came together and agreed to a large fiscal recovery package of just over €800bn. For the debt-laden periphery countries, the NGEU provides a well-needed reprieve. The ability to borrow at lower rates than they otherwise could themselves and the positive effect expected for nominal GDP growth may improve their debt sustainability

Owning EU bonds, additionally, reduces the risk of a collapse in confidence in sovereign debt because they act as a common safe asset, the value of which is more resilient to an idiosyncratic shock.

However, on the flip side, lower borrowing costs may encourage some countries to take on more debt by investing in more, potentially less efficient, projects.

Conclusion

For now, most countries are on a positive path for debt sustainability despite large budget deficits thanks to high inflation and lagging low interest rates. However, this situation will likely worsen as inflation comes down, real growth deteriorates and higher ECB rates feed through into government financing costs.

Despite this, the projected path for national debt and the factors determining this path look much more positive now than they did 14 years ago.