Achieving Gender Equality in South Korea

Part 5 of our Nomura - University of Sheffield research on the social pillar of ESG in East Asia examines gender balance across top companies in South Korea and reveals the industries most favorable to women.

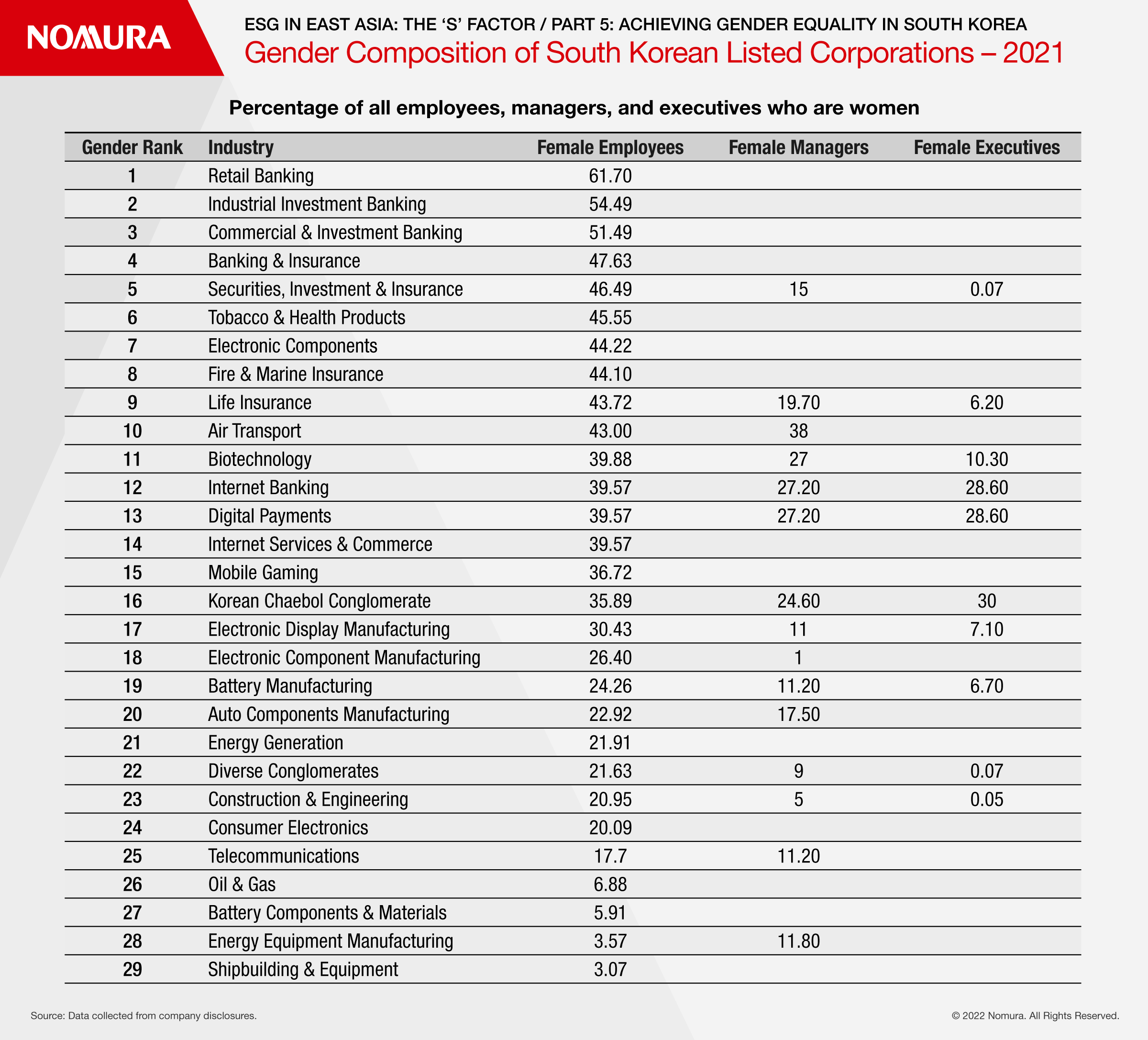

- Retail banking has the most female employees

- Internet banking and digital payments boast the most female managers

- Companies need to be less risk-averse to achieve better gender equality

This article was produced in collaboration with

Introduction

Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) in employment is essential for achieving sustainable organizations and, consequently, a sustainable society and environment. Hence, a commitment to maintaining high quality employment standards is the foundation-stone for upholding the whole ESG framework. These are the rationales underlying the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment.

In article four of our series on the ‘S’ Factor in East Asian ESG, we showed that employment diversity strategies would expand the pool of available high-quality employees at a critical juncture in South Korea’s economic development. Whereas labour appeared abundant during the region’s 20th century ‘catch-up’ phase of rapid economic expansion, prompting analysts to coin the term ‘demographic dividend’, in the 21st century every East Asian country faces an ageing and a shrinking workforce, and competition to recruit and retain the best employees amid a prolonged labour shortage. East Asian governments’ strict Covid-related migration policies have also made the situation more challenging.

DEI within organizations is not just a principle we should embrace for its ethical considerations. It creates a better working environment, promotes well-being and a sense of belonging, and it makes good business sense. It better enables companies to connect with customer needs and tastes, it generates higher levels of employee engagement, and it fosters innovation in thinking and practice, which enables companies to expand into and capture new markets.

East Asia's Gendered Employment Problem

Achieving gender balance across the whole organization is the biggest diversity challenge facing East Asian companies right now, and is an issue that knowledge-seeking ESG investors should be looking at with increasing concern.

East Asia’s gendered employment problem is holding companies back from achieving their potential. Despite decades of legislation and action to promote gender equality the situation is changing only very slowly. In the postwar era, both Japan and South Korea relied on a route to economic development rooted in enculturated notions about the complementarity of difference between women and men, which helped to structure a gendered division of labour across society. This enabled men to work very long hours in their organizations, while women provided support in the home.

In the 21st century the world is changing, however, and employers are adopting principles of universal justice, which demands equal opportunity regardless of inherited attributes.

Gender in South Korea Companies

Published this July, the WEF Global Gender Gap Report for 2022 provides uncomfortable reading for East Asian political and corporate leaders. Among 146 countries scored, Japan ranked 116th, and South Korea 99th. In the crucial economic participation and opportunity sub-index, Japan and South Korea lagged further, lying 121st and 115th respectively. But, how do South Korean companies fare when compared against each other and by industry?

We harvested data from the 50 largest listed companies in South Korea, with table 1 showing their gender composition at three levels – employment, managers, and executives. Among them, 29 provided this information in quantitative form in their ESG and sustainability reports. Of those, 15 provided data on female managers, and 10 on executives. The rest provided qualitative information and future oriented aspirational language without concrete substantiation.

We found considerable inconsistency between companies on their definitions, which further complicates our ability to analyse. For example, some gave employment numbers, but no data on gender composition, some included non-regular workers within their total employment, and companies had varying definitions of manager or executive.

As we explained in article three of our series, there is an urgent need for greater information provision, transparency, and standardization from South Korean companies regarding their ESG performance. Where companies’ reporting lacks clarity on women’s inclusion and progression, this could be a concern for responsible investors.

Finance and insurance companies are both the most data transparent and the best employers of women among South Korean listed companies, with some firms achieving greater than 50% inclusion. However, we caution that it is likely that non-regular employees – meaning part-time and temporary workers – may be included in these data, since some companies show female participation at greater than 50% of total employment.

The next best sector for female employment is internet, information and media, with around 30% or more inclusion, and here we are more confident that non-regular employees are not counted. As expected, traditionally male employment sectors, such as manufacturing and construction, and energy and chemicals, do less well.

Despite younger women outperforming men in education, South Korean companies often employ large numbers of single women in routine roles in the expectation that some will resign as their personal and family lives develop. Often they will return to the labour force after rearing their families, but in non-regular employment. Finance and insurance commonly adopt these practices, though they are changing, as our data shows on managerial and executive inclusion.

Known as statistical discrimination, this is a deep-seated East Asia wide problem, where the tendency is for employers to be risk averse in their hiring due to the costs associated with human capital development under a very long-term, or permanent, employment system in large organizations. We will look at human capital development later in our series.

Conclusion

Commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion is not just the right thing to do, it also promotes good leadership and a smarter business, and therefore enhances financial performance. A diverse organization makes good sense from the perspective of all stakeholders.

Overall, South Korean companies have a great deal to do to achieve gender balance across their organizations, to hire women into core roles, retain those workers, and promote them into managerial and executive roles. There is also more to be done in terms of transparency and clarity in data disclosure.

Download a PDF of the full whitepaper

Contributor

Dr. Peter Matanle

Senior Lecturer, School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield

Jim McCafferty

Head of Asia ex-Japan Research

Jing Wang

PhD Candidate, University of Sheffield

Yejin Shin

PhD Candidate, University of Edinburgh

Disclaimer

This content has been prepared by Nomura solely for information purposes, and is not an offer to buy or sell or provide (as the case may be) or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell or enter into any agreement with respect to any security, product, service (including but not limited to investment advisory services) or investment. The opinions expressed in the content do not constitute investment advice and independent advice should be sought where appropriate.The content contains general information only and does not take into account the individual objectives, financial situation or needs of a person. All information, opinions and estimates expressed in the content are current as of the date of publication, are subject to change without notice, and may become outdated over time. To the extent that any materials or investment services on or referred to in the content are construed to be regulated activities under the local laws of any jurisdiction and are made available to persons resident in such jurisdiction, they shall only be made available through appropriately licenced Nomura entities in that jurisdiction or otherwise through Nomura entities that are exempt from applicable licensing and regulatory requirements in that jurisdiction. For more information please go to https://www.nomuraholdings.com/policy/terms.html.